The first appearance of a house at Fonthill comes in 1533, when Sir John Mervyn purchased the estate and lived in a house surrounded by a park. A hundred years later Fonthill House was owned by Lord Cottington, Chancellor of the Exchequer in Charles I’s reign. He built a wall around his park and commissioned an impressive stable block. During the Civil War, the estate was given by Oliver Cromwell to John Bradshaw, Lord President of the parliamentary commission that tried the king. The Cottingtons returned to Fonthill when Charles II was crowned in 1660.

History

Fonthill House c.1680

Fonthill House c.1750

The house, and the estate were sold to Alderman William Beckford, Lord Mayor of London, in 1745. He redesigned the landscape, building a bridge, a temple (a banqueting house) and a pagoda. He also demolished St Nicholas’ church which was close to the house and rebuilt it on the site of the present Holy Trinity church at Fonthill Gifford.

But within 10 years the house burned down. A new house was built by him, known later as Fonthill ‘Splendens’. He also built the archway to form a grand entrance to his estate.

Fonthill Splendens

Fonthill Splendens by Hendrik Frans de Cort, c.1791

Splendens’ was built near the site of the old house, and this was the property inherited by his son, the notorious William Beckford, in 1770. He was the author of “Vathek”, builder of Fonthill Abbey and called by Lord Byron “England’s wealthiest son”. He developed the Park, extended the Lake and built the grottoes, the boathouse and a walled kitchen garden.

William Beckford decided to build Fonthill Abbey on high ground a mile south-west of Fonthill House in deep woodland and away from public roads. He demolished large parts of Splendens to provide building materials for his new Abbey, set in 524 acres surrounded with a wall 12 feet high.

He commissioned James Wyatt to build the Abbey in 1796 and it took many years to complete, housing his superb collection of furniture and antiquities.

Fonthill Abbey

Ruins of Fonthill Old Abbey

In 1823, William Beckford sold the estate to John Farquhar, a gunpowder contractor from Bengal, India. Within 2 years of this sale Fonthill Abbey fell down and Farquhar tried to sell all his land but died in 1826 intestate.

Farquhar had given the Pavilion, the only remains of ‘Splendens’, to his nephew George Mortimer who enlarged the house, built a new stable block and a woollen mill at the southern end of the lake. Mortimer tried to sell this ‘Fonthill Park’ estate in 1829. The sale particulars described the estate in glowing terms: “If Elysium can be contemplated on earth, the claims of Fonthill will be irresistible.” The landscape of the estate is still considered an “Arcadian idyll”.

In the summer of 1829, the Pavilion was rented to James Morrison and his growing family. The holiday was a great success and he bought the property from Farquhar’s heirs – the Mortimers – after protracted legal difficulties.

James Morrison had by this time become a very successful haberdasher and entrepreneur in London with a house in Harley Street and a seat in the House of Commons as Member of Parliament for Ipswich and later the Inverness Burghs. He was described at the time as the “Napoleon of Shopkeepers”. He improved his parkland, repairing Beckford’s grottoes and building some cottages. In 1837 his agent wrote to him that visitors to Fonthill went on to Stourhead, then, on returning, ‘told me that Stourhead was not worthy to be compared to Fonthill.’

By 1844, the Fonthill Park estate had ceased to be his main country home. He had bought Basildon Park in Berkshire (now National Trust). His commitments as MP, investment banker and haberdasher “extraordinaire” were extensive and he had found Fonthill too distant from London, the coach taking 11 hours.

The Pavilion c.1828

The Pavilion, renamed Fonthill House c.1890

Morrison gave Fonthill to his second son Alfred, who lived in it all his life with Mabel his wife and family. The house was enlarged in 1846-48 by David Brandon, who raised it by one storey and added an Italianate tower. Alfred engaged Owen Jones to design the interior and added three galleries to house his growing collection of paintings, sculpture, china, medals and manuscripts. Alfred also built a number of cottages on the estate and, in 1875, bought Great Ridge Wood from Edmund Fane of Boyton.

Much of the western part of Beckford’s estate, including the site of the Abbey, was not acquired by James Morrison. It was eventually bought by the Marquess of Westminster, who by 1859 had built what was then called Fonthill Abbey, 500 metres south-east of Beckford’s fallen folly. This house designed by William Burn in Scottish baronial style was demolished in 1955.

Fonthill New Abbey

Fonthill House Little Ridge

Alfred Morrison’s son Hugh inherited in 1897 but Alfred’s widow Mabel continued to live in the old Fonthill House/ Pavilion. Hugh consequently built a new house called Little Ridge, on land on the other side of the lake, in the Parish of Chilmark. It was designed by Detmar Blow who moved the semi-ruined 17th century manor house of Berwick St Leonard, stone by stone, to the new site to form the centre of the house. Wings were added just before and after the First World War, then, in 1921, the old Fonthill House/ Pavilion was demolished, and Little Ridge was renamed Fonthill House.

This Fonthill house was mostly demolished in 1971, by Hugh’s eldest son John Morrison, lst Lord Margadale. He replaced it in 1972 with a smaller, more economical house, in classical style, designed by Trenwith, Wills and built on the centre block of its predecessor.

The estate first bought by James Morrison in 1830 consisted of 1200 acres. It is now 9000 acres. It descended from Alfred (died 1897) to Hugh, MP for Salisbury (died 1931), then John, MP for Salisbury, made Lord Margadale in 1964. His eldest son James, 2nd Lord Margadale, inherited in 1996 and died in 2003. It is now owned by his eldest son Alastair, 3rd Lord Margadale.

THE HISTORY OF THE MORRISON FAMILY

- James Morrison. the founder of the family fortunes, was born in 1789 in modest circumstances in the Lower George Inn, Middle Wallop, Hampshire. By the time he died in 1857 he was one of the most successful but least known merchant millionaires. He went to London as a youth, both parents having died, became apprenticed to a retail haberdasher in Fore Street in the City of London and married his boss’s daughter.

- Within a few years he had shown his genius for making money and had been dubbed ‘the Napoleon of shopkeepers’. By 1830 his business, by then a wholesale haberdashery, had a turnover of nearly £2 million per year, the equivalent of £200 million today. He invested large sums in American companies, particularly railways, was involved in global trade and bought land, houses and works of art in unbelievable quantities. He became a Member of Parliament for various constituencies, including the Inverness Burghs, for nearly 20 years and moved in the highest circles.

- When James died, all his ten surviving children were left fortunes and his six sons inherited extensive country estates. Three of his sons, Charles, Alfred and Walter either added enormously to their wealth by their investments or created huge collections of autograph letters of famous people and objets d’art of great importance. Of James’ estates, Basildon in Berkshire and Malham in Yorkshire were sold in the 1920’s by one of his grandsons- James Archibald – but an enlarged estate at Fonthill and part of the island of Islay in Argyllshire continue to this day in the family’s possession.

- Six of James’ male descendants have been Members of Parliament and Charles and Walter gave away huge sums of money in their lifetimes to a wide variety of charities. John Granville Morrison, James’ great grandson, 1906-1996, inherited the Fonthill estate and a large house, called at first Little Ridge, built by his father Hugh. This was to become the fifth house on the estate to be pulled down or replaced and the current house dates from 1972. Having been M.P. for Salisbury since 1942 and Chairman of the Conservative Party’s 1922 Committee for over 10 years, he was raised to the peerage in 1964 as Baron Margadale of Islay. A photograph of the Morrison and Todd family tree is attached.

- See Dr. Caroline Dakers: ‘ A Genius for Money — Business, Art and the Morrisons’, published in 2011 by The Yale University Press, for a very informative and comprehensive study of James Morrison’s life and that of the eldest two of his seven sons up to 1909.

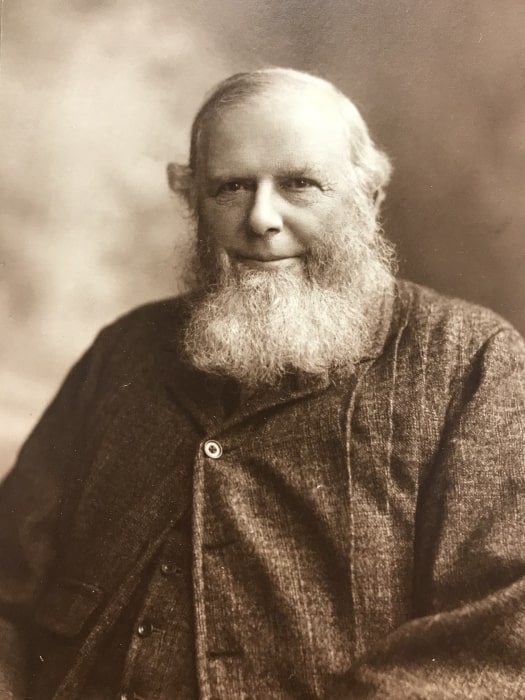

James Morrison

1789—1857

Mary Ann Morrison

née Todd

1795 -1887

Charles Morrison

1817—1909

Alfred Morrison

1821—1897

Mabel Morrison

née Chermside

1847—1933

Walter Morrison

1836—1921

Hugh Morrison

1868 — 1931

Archie Morrison

1873 – 1934

Dorothy Morrison

Viscountess St Cyres

1871—1936

John Granville Morrison

First Lord Margadale

1906—1996

James Ian Morrison

Second Lord Margadale

1930—2003

Alastair John Morrison

Third Lord Margadale

Henry William Pickersgill, James Morrison 1824 & Mary Ann Morrison 1824 by kind permission of the trustees of the Walter Morrison collection of Sudeley Castle

THE ARCHIVES AT FONTHILL

- The archives are very extensive, now catalogued on an ADLIB database and shelved in 290 large boxes in the Archive Room at the Fonthill Estate Office. There are nearly 3000 catalogue entries, some very substantial.

- The personal, family ,19th century estate and business elements of the archive of James and many other members of the family spent most of their life up to 1970 in the Morrison Estate Office in Coleman Street, London, and survived both world wars intact. They were then brought down to Fonthill in nearly 100 tin trunks and tea chests and resided in the old kitchens in the basement of the newly rebuilt Fonthill House. It was there that Richard Gatty, James Morrison’s first biographer and second cousin of John Morrison, and a few other hardy researchers, including Caroline Dakers, struggled to find the material they needed for their biographies. By 2007 the archives had arrived at the Estate Office in Fonthill Bishop.

- The later Fonthill Estate records, which survived Mabel Morrison, Alfred’s widow, and her presumed archival destruction, and which had probably been maintained locally by the estate’s agents in Salisbury, accumulated in the Estate Office or in the Old Creamery at Berwick St. Leonard Farm, until gathered in for appraisal and cataloguing between 2007 and 2012.

- James Morrison appears to have been ordering his papers in the last years of his life in preparation for writing his memoirs, because various correspondence was copied out, relating to his take-over of his father-in-law’s haberdashery business, and through other signs, but the writing stage was never reached.

- The content and range of the collection matches the typical country house estate archive of its time, but with three substantial and very untypical elements—– those of recording James the exceptionally successful businessman, banker and politician and the multi-millionaire acquirer of landed estates, pictures and objects. All the usual parts of a family archive are here, deeds of property, family letters, personal account books, estate accounts and papers, a very few estate maps and plans, photographs and very extensive probate and executorship papers. There are good series of records for James’ management of the Fonthill and Basildon estates up to his death, but they are poor thereafter, until the 20th century at Fonthill.

- Two other estates are well represented in the surviving archives, that of Islay, Argyllshire, Scotland, from the 1890’s, now largely, but not entirely, in the Mitchell Library, Glasgow, and here in these archives that of Walhampton, Boldre, Hampshire, the country home of Dorothy Morrison, Viscountess St. Cyres, one of James’ granddaughters, who left this estate to Charles Andrew Morrison, John Morrison’s second son. For the estates of the other children of James, after they had inherited and sold them, there is very little here.

- The unusual elements in the archive are extensive and should provide useful material for research. The papers of James Morrison’s haberdashery business in Fore Street, London, have survived well, although there were 6000 account books probably destroyed when the firm was sold in the 1860’s. The banking and investment business is represented in thousands of letters and should be of interest to historians of the growth of trade and industry in North America and elsewhere.

- James Morrison was an M.P. for three constituencies and had interests in a number of others. He considered himself ‘an independent member’ and in Parliament was recognised for his commercial expertise, which developed particularly around railways. He later turned down a baronetcy, considering it a poor investment. These archives are full of documents of a wide variety illustrating his thirst for information, having had no formal education in his youth.

- His collecting interests are well represented in his papers, with accounts and letters from art dealers and artists and comprehensive inventories in his diaries and prepared by a contemporary art historian. In contrast, what survives for Alfred, who inherited his father’s collecting instincts and took them to much more intensive levels, is far less in quantity and except for the huge inventories of autograph letters, medals and coins and a modest batch of accounts, this is a disappointing series. The surviving archives for Charles, who died with one of the biggest investment portfolios ever known at the time, consist largely of his writings about capitalism, Darwin and suchlike, and papers and ledgers about his worldwide share holdings.

- In the 20th century, John Granville Morrison left little surviving of his political work, but one of the interests closest to his heart -hunting- is well illustrated by the substantial South and West Wilts Hunt records, as is the record of the steady increase in size and development of the Fonthill estate in his period. This reached its peak in size at 11,000 acres in the 1960s.

- John Morrison’s youngest son Peter, who became a Conservative M.P. for Chester and Mrs. Thatcher’s Parliamentary Private Secretary in the last years of her premiership, in addition to various earlier ministerial posts, has left detailed papers of his work and in particular of her standing for election for the leadership of the Conservative Party in 1989 and 1990, which are important.

WHAT’S MISSING FROM THE ARCHIVES

- James Morrison’s presumed intention to write his autobiography has secured the survival of his archives to a very large degree and his descendants probably saw them as too important to their family history to let go. It is very likely that his widow Mary Ann, who outlived him by 30 years, and their eldest son Charles may have removed his very personal records.

- Charles, his eldest son, the inheritor of Basildon in Berkshire, has left little personal material, except his substantial draft works of philosophy and religion. All of his estate archives were probably destroyed when Basildon was sold in the 1920’s, by his much married and extravagant nephew, James Archibald. Almost everything since 1857, when James died and its sale in the late 1920s to the Iliffes, is not in this collection, except for a few items kept by the Estate Office in London and now here or in the Berkshire Record Office.

- Alfred’s management of the Fonthill Estate between 1857, his death in 1897 and his son Hugh’s succession until his death in 1931 is very little recorded, probably because estate agents were used, and few papers may have resided at Fonthill itself. If they had been kept by the London office, they would probably have survived. The disappearance of Alfred’s personal papers relating to his collections of autograph documents, engravings, coins, medals, porcelain, glass, metalwork and enamels and the rebuilding and redecoration of Fonthill House and 16, Carlton House Terrace in London is a far greater loss. This was probably affected by his widow, Mabel, who outlived him by nearly 40 years and lived in their matrimonial home at Fonthill for 20 years after his death, with only the catalogues of his collections and a few acquisition papers still in existence.

- James Archibald’s life was so much spent on the move, hunting and shooting big game, fighting in military campaigns and changing wives; his occupation of Basildon and the management of the estate, after his uncle Charles’ death, was so transient, that it is not really surprising that few of his papers survive. ‘Modern’ country house archives before the opening of County Record Offices were very vulnerable.

- From the 1920’s, when John Granville Morrison took on the management of Fonthill, the survival of estate archives improves dramatically, although he authorised the destruction of most of his Salisbury constituency records after he retired from Parliament in 1964.

- For genealogists seeking the stories of their ancestors working on the family’s estates, the survival of personnel records is very patchy indeed and little of any consistent regularity exists from before 1920. One remarkable survivor is a photograph album of all the Fonthill Estate employees, made for Hugh Morrison, when he came of age in 1889. But the separate key to the names of those photographed, some probably for the only time in their lives, has not yet come to light.

ARRANGEMENT OF THE CATALOGUE

- The archives were catalogued between 2008 and 2012 and are arranged largely by using as a structure the individual members of the Morrison family, from James the founder to Alastair, the third Lord Margadale. Within each family member’s ‘fonds’ or section, given a letter of the alphabet from A to Y, there are a series of numerical sub-divisions or ‘series’, dividing up the archives into coherent and related sub-groups, such as property, personal, business, estate management and other individual selections.

- The ‘fonds’ are as follows:

Section A – 1788 – 1857: James Morrison – Includes his wife Mary Ann Todd

Second Generation

Section B – 1817 – 1909: Charles Morrison

Section F – 1821 – 1897: Alfred Morrison

Section G – 1847-1933: Mabel Chermside later Morrison, Alfred’s wife

Section H – James’ Other Children

Section J – 1834 – 1909: Ellen Morrison

Section K – 1836 – 1921: Walter Morrison

Section L – 1839 – 1884: George and Allan Morrison

Third Generation – 1842-1880

Section M – 1868 – 1931: Hugh Morrison

Section N – 1870 – 1934: Lady Mary Leveson Gower, later Morrison, Hugh’s wife

Section O – 1869 – 1949: Katharine Morrison, Lady Gatty

Section P – 1871 – 1936: Dorothy Morrison, Viscountess St. Cyres

Section Q – 1873 – 1934: James Archibald Morrison – Includes his wives

Fourth Generation

Section R – 1903 – 1969: Simon Archibald Morrison

Section S – 1906 – 1996: John Granville Morrison, First Lord Margadale

Section T – 1908 – 1980: Hon. Margaret ‘Peggy’ Smith, Lady Margadale

Section U – 1910 – 1992: Marjorie Morrison, later Egerton

Fifth Generation

Section V – 1930 – 2003: James Ian Morrison, Second Lord Margadale

Section W – 1944 – 1995: Sir Peter Hugh Morrison M.P.

Sixth Generation

Section X – 1958 – : Alastair John Morrison, Third Lord Margadale

FONTHILL ARCHIVES

The Fonthill Estate Archives are privately owned records generated and amassed by Lord Margadale, the Trustees of the Fonthill Estate and their predecessors. They are located at the Fonthill Estate Office in Fonthill Bishop.

Enquiries about the archives and their content can be directed to the Archivist at Fonthill via the Estate email mail@fonthill.co.uk or jdarcy102@gmail.com. The Archivist attends at the Estate office intermittently.

The complete Introduction can be found digitally in the National Archive (TNA) website, in their Discovery Section at www.nationalarchives.gov.uk from where questions can be forwarded here via their staff.

Charges or access fee

A charge of up to £40 per hour including VAT will be made to enquirers seeking extensive research work by the archivist or for his attendance in person at the Fonthill Estate Office in Fonthill Bishop, when the enquirer needs extended periods of research and invigilation by the archivist.

Students registered on a recognised course are exempt from any fee.

The level of charges for other researchers may be reduced where the research adds considerably to the knowledge of the Fonthill Estate.

Copyright

Copyright of all material including digital images is retained by the Fonthill Estate.

Application for permission to publish information and illustrations should be made to Lord Margadale through the Archivist, and acknowledgement should be made in the text that publication is “By permission of Lord Margadale and the Trustees of the Fonthill Estate”.

Photography

Photography is permitted. The use of flash photography or hand-held scanners is not allowed. Researchers must complete a photography form giving details of images taken. Photographs must only be used for non-commercial research or private study and may not be reproduced or published without prior permission from the Estate.